formationhas not. Both formationswere probably

deposited in the same back-arc basin at

c.

521–

506 Ma. The first sediments deposited were those

of the Banded Gneiss formation (due to its higher

isotopic heterogeneity and higher presence of

intruded igneous rocks), formed by the mixture

of the old components from the WAC (Eburnean

and Archean detritus) and abundant arc-related

c.

590–520 Ma sediments. The Cariño Gneisses

protoliths deposited afterwards, filling the same

basin with WAC sediments and abundant

c.

560–

510 Ma arc-derived sediments.

When the sediments of these formations were

deposited, igneous rocks intruded in the Banded

Gneiss formation. The first igneous materials to

intrude were the acid magmas, the protoliths of

the orthogneisses, at

c.

512 Ma, and afterwards

the basic magmas at

c.

505 Ma (Fig. 2). Some of

the basic magmas are clearly juvenile additions

to the crust derived by partial melting of a

depleted mantle source. Others, however, have

more enriched isotope signatures, which are

interpreted as a partial fusion of an enriched

mantle component (probably the subcontinental

mantle of Gondwana), or as an important

contamination of a DM-derived partial melt

with continental crust material. The sources of

the acid magmas probably divers from depleted

to isotopically enriched sources. The intrusive

processes continued in the magmatic arc, and

at

c.

498 Ma the orthogneisses show their zircon

crystallisation climax. At this time the arc activity

induced high-T related metamorphism that

partially melted previously generated igneous

rocks (generating acid rocks by partially melting

basic rocks) until

c.

460–470 Ma. Due to this high

temperature input the sediments partially melted,

migmatising at

c.

495–485 Ma (Fig. 2). The basic

rock´s zircon crystallisation climax occurred at

215

9. FINAL DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Ͳϱϱ

Ͳϰϱ

Ͳϯϱ

ͲϮϱ

Ͳϭϱ

Ͳϱ

ϱ

ϭϱ

Ϯϱ

ϯϬϬ

ϯϱϬ

ϰϬϬ

ϰϱϬ

ϱϬϬ

ϱϱϬ

ϲϬϬ

ϲϱϬ

ϳϬϬ

ϳϱϬ

ϴϬϬ

^ĞĚŝŵĞŶƚƐ ; ĂƌŝŹŽ н ĂŶĚĞĚͿ н ŽƌƚŚŽŐŶĞŝƐƐĞƐ н ĞĐůŽŐŝƚĞƐ н ůĞƵĐŽƐŽŵĞƐ

^ĞĚŝŵĞŶƚƐ ;

Ŷ

с ϯϮϭͿ

KƌƚŚŽŐŶĞŝƐƐĞƐ ;

Ŷ

с ϭϱϳͿ

ĐůŽŐŝƚĞƐ ;

Ŷ

с ϳϲͿ

>ĞƵĐŽƐŽŵĞƐ ;

Ŷ

с ϭϬϲͿ

İ+I

W

8 3E DJH >0D@

&DGRPLDQ FUXVW

(EXUQHDQ FUXVW

$UFKHDQ FUXVW

+DGHDQ FUXVW

ϱϬϬ

7 PRGHO DJH

'0

&UXVWDO HYROXWLRQ WUHQG

/X +I

'0

&+85

ϳϬϬ

ϲϬϬ

ϰϬϬ

025% '0

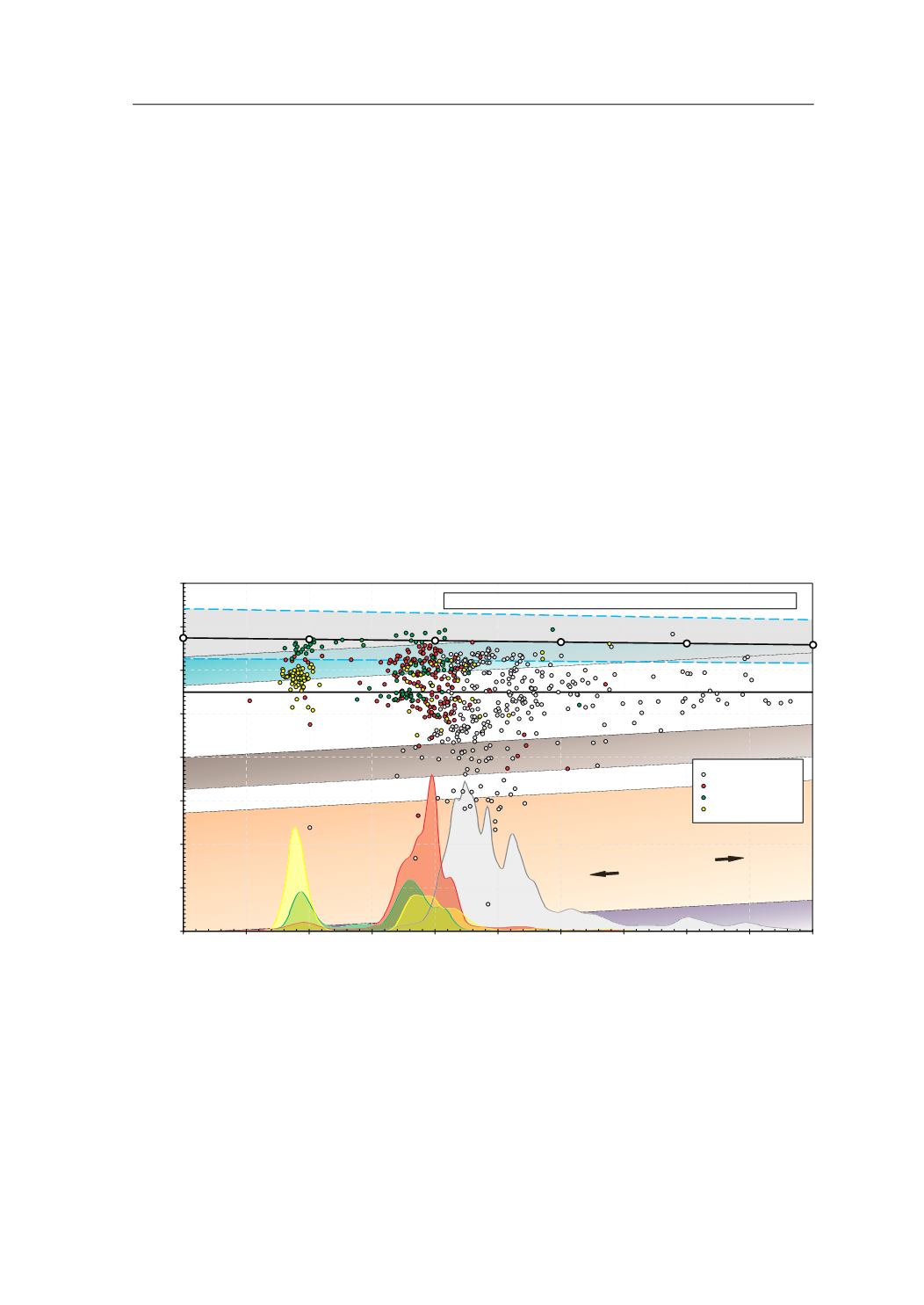

Fig. 2.

H

Hf

v

. age diagram for all the lithologies studied. Density plots at the base of the figure are adaptative Kernel Density

Estimations (aKDEs) for each of the lithologies studied (grey: sediments; red: orthogneisses; green: eclogites; yellow:

leucosomes). The four aKDEs have been normalized to the same histogram bin heights (histogram diagrams of the U–Pb

analyses that have their corresponding Lu–Hf analysis represented in this figure. Histogram diagrams are not represented,

and have been calculated with DensityPlotter5.0, Vermeesch 2012; bandwidth = 5 Ma, binwidth = 5 Ma). Coloured inclined

shaded areas represent crustal evolution trends for Hadean, Archean, Eburnean and Cadomian DM derived rocks. MORB

H

Hf interval was taken from the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian MORB values (excepting three unusual low values from the

Indian Ocean) reported by Chauvel & Blichert-Toft (2001) considering a minimum

H

Hf

(t=0Ma)

= +8.3 (

176

Hf/

177

Hf = 0.28302)

and a maximum

H

Hf

(t=0Ma)

= +20.7 (

176

Hf/

177

Hf = 0.28337). These values are propagated to

H

Hf

(t=4Ga)

= 0 defining a grey field

(enclosed by the blue discontinuous lines) around the DM-evolution trend, to provide an indication of the likely range of

DM compositions through time.

n

, number of concordant zircon analyses (90–100% conc.), analysed for Lu–Hf isotopes.

MORB: mid-ocean ridge basalts; DM: depleted mantle; CHUR: chondritic uniform reservoir.