174

176

Lu/

177

Hf ratios plot around 0.00144 ±

0.00134 (±2 SD; Fig. 63b).

176

Yb/

177

Hf ratios plot

around 0.0456 ± 0.0450 (±2 SD; Appx. 4).

Nd whole-rock model-age is 0.75 Ga and

H

Nd

(t)

values are:

H

Nd

(t=0)

= +2.5;

H

Nd

(t=485)

= +5.0.

7.4.2.2. Discussion

The U–Pb ages are spread between

c.

510 and

450 Ma, with a maximum abundance peak at 485

Ma (Fig. 60). The textures shown by the zircon

grains in this sample vary from “soccerball”, to

oscillatory, to transgressive recrystallisation

areas. These types of textures could not be linked

to specific age ranges or to any chemical variation

ratios. The only exception is the transgressive

recrystallisation areas, where two U–Pb analyses

were performed, with ages of 378

r

7 and 430

r

23 Ma (Fig. 61). These areas are interpreted as

to be the result of a solid-state recrystallisation

event dated in other samples at

c.

390 Ma. The

rest of the ages in this sample, that vary between

c.

510 and 450 Ma, show a wide spread in their U,

Pb, Lu and Yb contents. Their higher

H

Hf

(t)

values

plot in the MORB-depleted mantle field (higher

value: +9.2) and their lower values plot very near

the CHUR trend (lower value: +1.3; Fig. 62a).

Their

176

Hf/

177

Hf

(t)

values also present a high

variation and no tendency in their values was

found in relation to their U–Pb ages. This wide

range in their U–Pb ages and the wide range in

their chemical compositions can be explained

by a rejuvenation process via Pb-loss triggered

by the

c.

390 Ma recrystallisation event. This

explanation does not seem satisfactory due to the

very lowproportionof discordant analyses (2.5%)

and to the high concordance achieved by the U–

Pb zircon ages (69 out of 122 analyses are 98–

102% concordant). Another explanation could

be that the protolith magmatic material started to

crystallise zircon with high-T related “soccerball”

textures (

e.g.

A046 and A059; Fig. 61) and that

before the magmas completely crystallised they

were mixed with other magmas with different

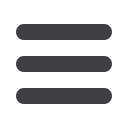

Fig. 59.

U-Pb conventional concordia diagram showing

U-Pb zircon analyses of the studied sample. Ellipses repre-

sent combined 2

σ

uncertainties of

206

Pb/

238

U and

207

Pb/

235

U

ratios.

n

, number of analyses considered (those with 90–

110% concordance)/total number of U–Pb analyses.

3E 8

GDWD SRLQW HUURU HOLSVHV DUH ı

3E 8

*&+

2UWKRJQHLVV

Q

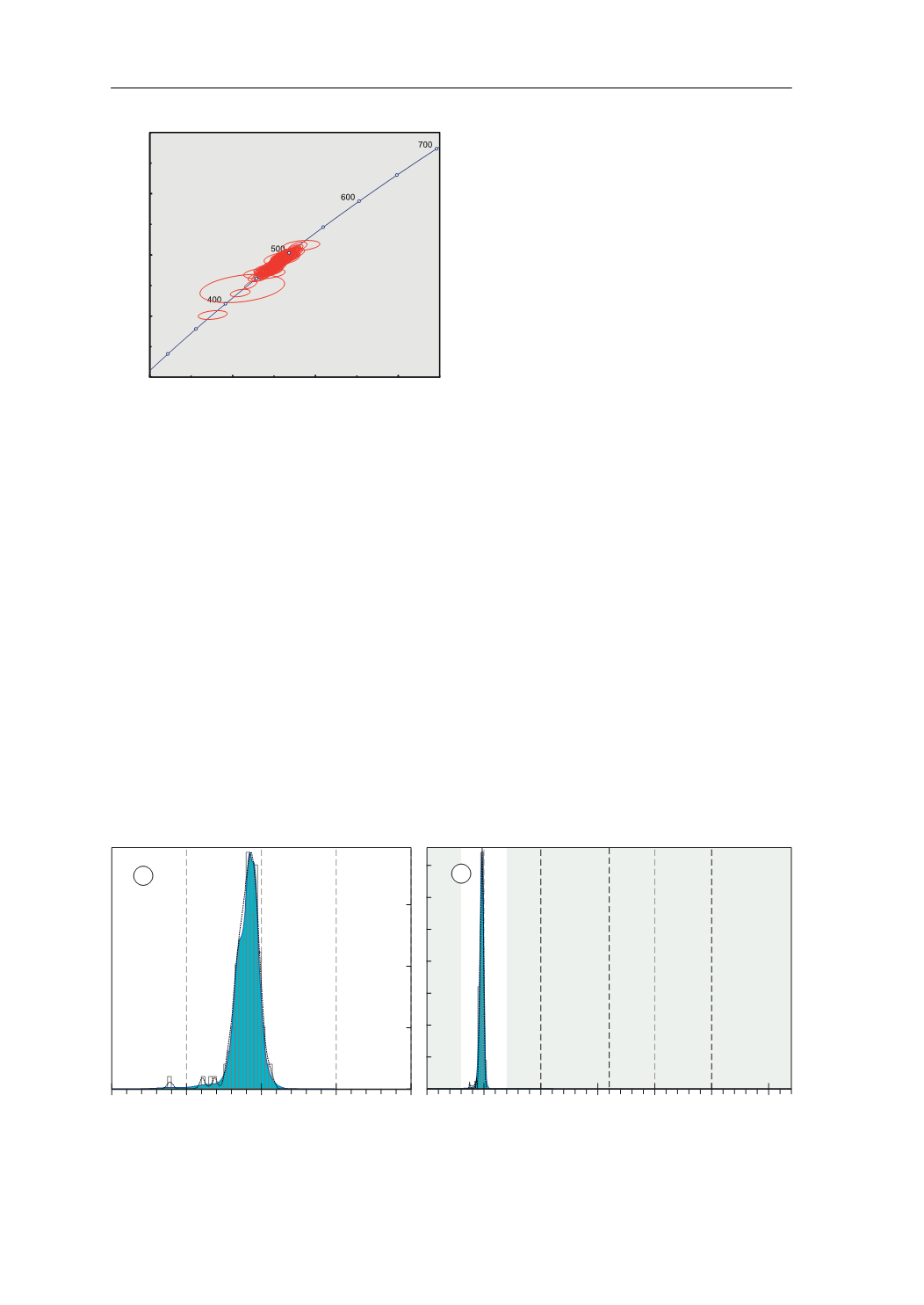

Fig. 60.

Adaptative Kernel Density Estimation (aKDE, continuous line enclosing the blue area), Probability Density (PDP,

black dashed line) and histogram diagrams of the U–Pb analyses (calculated with DensityPlotter5.0, Vermeesch 2012).

Numbers in the vertical axis represent histogram frequency;

n

, number of analyses.

a

Partial plot representing data within

a 300–700 Ma time range (bandwidth = 5 Ma, binwidth = 5 Ma).

b

Complete plot (bandwidth = 15 Ma, binwidth = 25 Ma).

3DOHRSURWHUR]RLF

0HVR

SURWHUR]RLF

3DOHR]RLF DQG

1HRSURWHUR]RLF

$UFKHDQ

>0D@

Q

Q

D

E

7.4. ORTHOGNEISSES